Creatives in Practice:

Kevin Morosky

“No Black woman is a monolith”

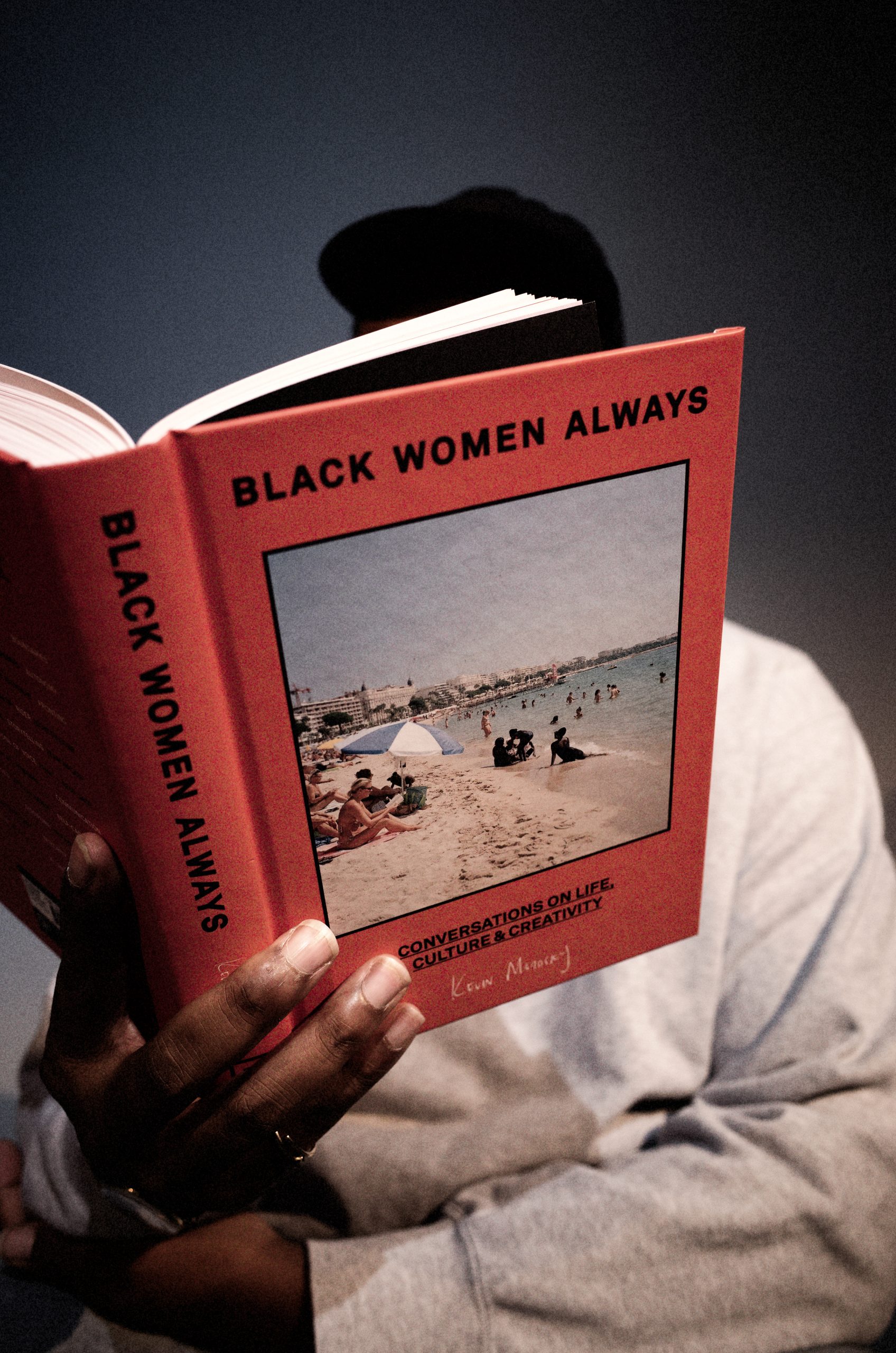

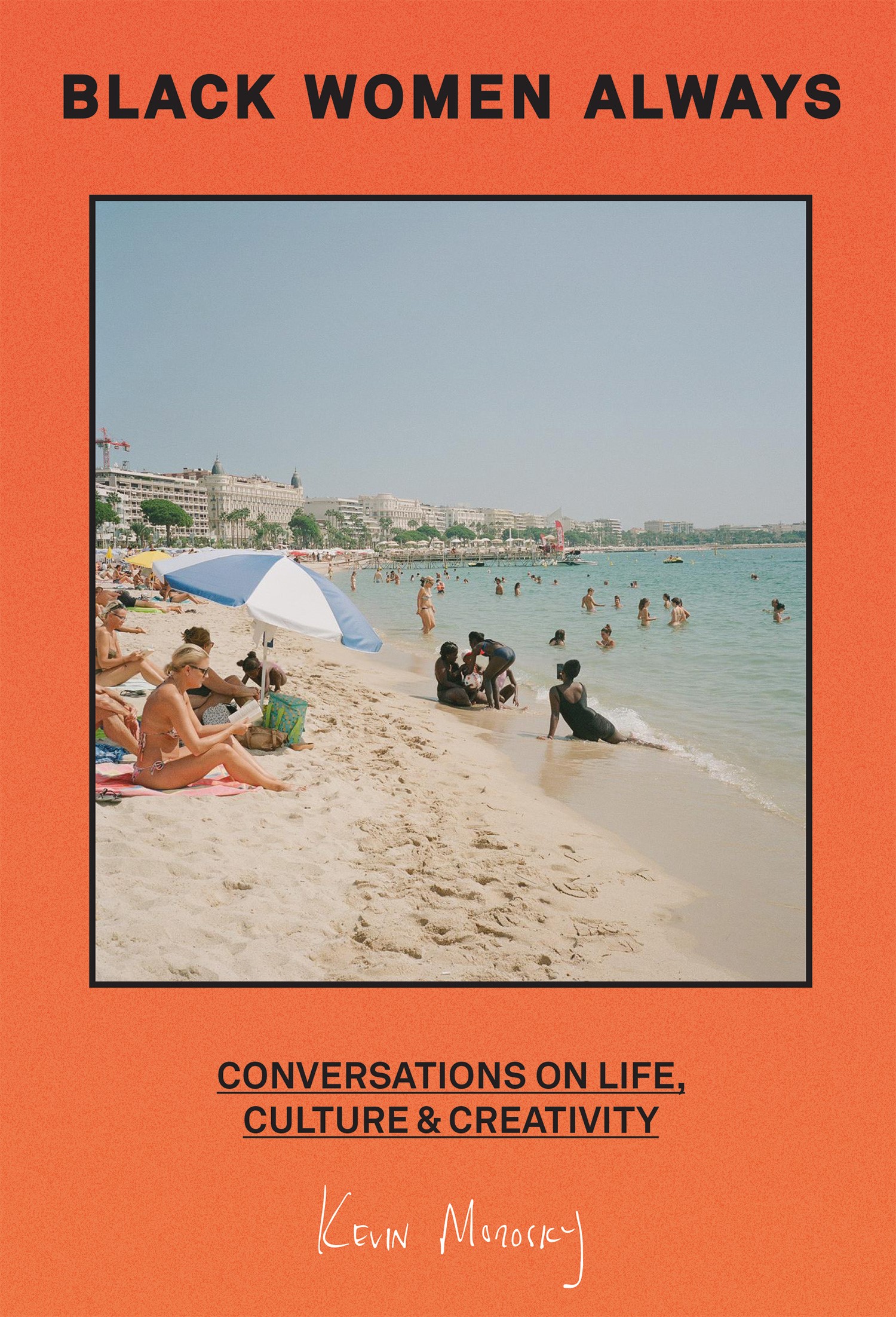

PAUSE sits down with the film director and author to discuss his upcoming book, Black Women Always: Conversations On Life, Culture And Creativity, a defining manual on using creativity for empowerment.

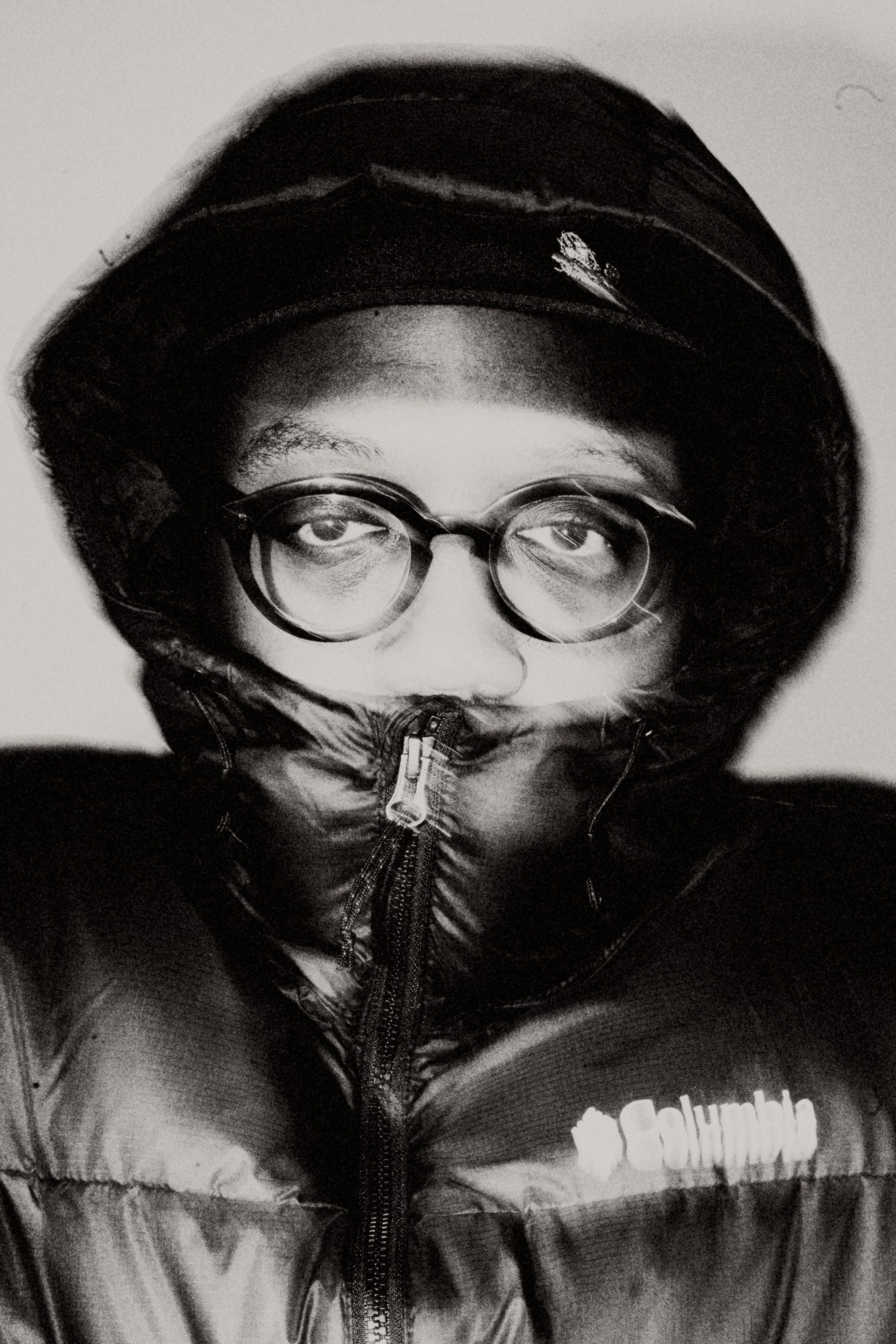

Kevin Morosky is booked and busy. But that’s hardly unusual for the creative polymath, whose diverse body of work includes the award-winning short film Bruce and ad campaigns for the likes of Netflix and the BBC. The South London native is also the co-founder of Pocc, a creative network that champions Black and Brown voices in advertising. Ahead of the release of Black Women Always (out 14th March) Kevin finds a quiet moment to reflect on his journey.

Interview: Jasmin Oakes | @jasminaliceo

Photography: Jemima Marriot | @jemimashoots and Chieska Fortune Smith | @chieskafortunesmith

You’re at the top of your game in many different fields. Was there a specific moment when you felt like you’d amassed enough knowledge and decided you were ready to share what you’ve learned from your lived experience?

I realised that I never stop learning or improving, but with that being said, what looks like mastery to others is just the beginning to someone else. The mentality of “when I get to this point, then maybe I’ll do this,” can be dangerous. I think it was just about being vulnerable and being really honest. I also think it was me moving away from advertising, which I’m still involved with to a certain extent through Pocc, but I’m now focusing on film and bringing together the things that I love the most. So it was almost like letting everything all out and starting afresh. I cut my hair off. When I started advertising, I had just started growing it out. For about eight or nine years, my locs were down to just below my elbow. When I finished the book, it felt like such a moment and I wanted to let go of all of the things that I’ve been through and all of the trauma. Even some of the stories in the book were traumatic. And so, when I did it, it was like an exorcism.

So it was a means of catharsis?

100%. Last year I also finished working on a short for Disney and the National Film and Television School called Gently. It was an incubator programme where directors and writers of all levels could come along and make a short within a particular budget. I did it with my creative partner, Tom [Dunn], and I went into that experience wanting to meet lots of amazing people and to be critiqued. To be honest, it was stressful working within a confined space, but also testing all of the things that I had learned. [Laughs] Somehow I was able to get through it. But it all happened around the time I stepped into the next phase of what I’m doing.

As someone who works so much within the digital space, why was it important for you to write this book, as opposed to other creative mediums?

I think growing up, the idea of me being in advertising or becoming a creative, an art director, and a storyteller wasn’t even an option. When I was at school we had a career day and someone told me I could be a cleaner. Looking back at that, I thought, “Wow, no one really looked at my tenacity or attention to detail and taught me how I could redirect my energy into a space and succeed.” There was one teacher, Ms Harvey, I think I mentioned her in the book, who told me, “You love to argue, but you’re also good at debating and telling stories—you just don’t do so well on paper.” She was one of the first to mention that I might be dyslexic, but it wasn’t until I got to the middle of secondary school that anyone really spoke to me about it. Some of my friends with dyslexia were given laptops and extra help, but it wasn’t afforded to me, all I got was detention. I don’t like to label myself as an activist, but I think we all do things that fall into that arena and are political. For me, as someone who is dyslexic, it was important to write this book. I’m not trying to be the best author in the world and I’m not trying to compete with anyone. I wanted to inspire someone so they think, “Oh my god, maybe I could do that!” because that’s the way that we connect. It’s community. We are all a living, breathing part of this culture that I speak about and it only keeps living and breathing as long as we are vulnerable enough to try our hand at something and also conquer a fear.

“We are all a living, breathing part of this culture that I speak about and it only keeps living and breathing as long as we are vulnerable enough to try our hand at something and also conquer a fear.”

You said in the introduction that you create so others can feel seen, heard, and remembered. Is that how you hope people will feel after reading your latest book?

It’s definitely all of those things, and it’s the way that Black women have always made me feel. I also liked the idea that if you’re not Black or Brown, there is no way for those conversations to be interrupted. I think there’s a really lovely space, specifically for white people, to take away from these conversations things they’ve never been able to hear because sometimes they’re busy trying to add to it when the only task at hand is to listen.

I have tried to uplift others and give them space to be who they need to be. In Kuchenga’s conversation on resilience, she says at the end, “I went to the right schools, and I sucked the right cocks.” I asked her if she wanted to keep that sentence in and she was like “I said what I said, that’s how I feel.” But I love that it came straight after my mother’s chapter because these are the conversations that are happening. I hope I’ve done justice and shown that no Black woman is a monolith. None of them exists in the same way, although there are crossovers through experience, trauma and love.

You spoke with such an inspiring group of women from all different walks of life, like Bianca Saunders, Shygirl, Candice Brathwaite and Lady Phyll to name a few. Is there anyone whose wisdom you benefitted from that you weren’t able to sit down with?

My grandma. [Pause] Not me about to cry in this interview. She was the most wonderful person, she really was. [Laughs] I’m sorry.

It’s okay.

But my crying at this moment means that I still remember her deeply and that she’s still with me. The day that I don’t get upset like this I’d be worried. That’s why in Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu’s chapter, I started crying because she’d just cut her hair and looked like my grandma, so it felt like I was talking to her and seeing her again.

What did you learn from your grandma?

She was just honest, very “I said, what I said and this is how I feel.” She taught me to be good to people and take time with them. She never rushed to judge anyone. She gave without waiting to receive and she was kind because it was the right and honest thing to do, not for the payoff down the line. I think that just shows up in everything that I try to do, whether it’s through Pocc or my creative philosophy. I’m not trying to be the king of anything. There’s space for everybody. I’m just adding my voice to the rainbow of voices, so more people can be inspired and find themselves. I’m so happy to be part of that.

“There’s space for everybody. I’m just adding my voice to the rainbow of voices, so more people can be inspired and find themselves. I’m so happy to be part of that.”

There are key takeaways at the end of each chapter, like the importance of intuition and diverting energy towards yourself. This might be like choosing your favourite child, but can you single out which one has had the biggest impact on your life?

I think I have two. Intuition. As you know, I’m a Virgo and so I feel everything in my gut. I remember in my younger years, walking into situations where my stomach was going crazy and it felt wrong, so I left. And afterwards, I’d hear that there was an incident that could have taken me out. But unfortunately, we live in a society that from my experience, makes the idea of us listening to our bodies or that inner voice seem strange. Also, the conversation with my mum helped me heal in certain places. It got me thinking about the perspective that I had as a school kid and I was able to look back at things that had happened with adult eyes and try to merge the two.

You took the photo that appears on the book’s front cover. What was it in particular that struck you when you decided to take the shot?

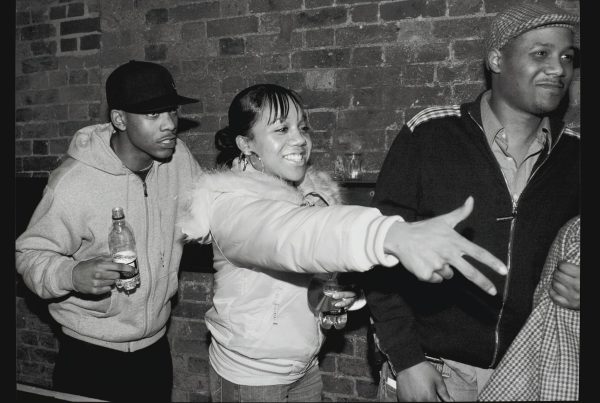

At the beginning of the book, I spoke about my time at the Cannes Lions Festival and there was a beach event dedicated to Black, Brown and global majority creators, and I found it so depressing. There was this constant energy, where Black and Brown people were being questioned on their right to be in that space. When the festival ended, I stayed for an extra day or two and when I was at the beach, I saw these Black women having the best time. I thought, “Oh my god, there’s just no one else here who is Black or Brown.” There was just me behind the camera, the women and everyone else was white. So I took the picture, not even knowing if I got it because I shot it on film. Years later, when my publishers came to me with two cover options, I knew exactly how I wanted it to look but I didn’t know what the image was going to be. So I considered going off to shoot all these other things. But then I remembered the photo I took and it was perfect. You can see that the Black women in the shot are just trying to make joy, and even though they’re in the minority, they’re still confident and having the time of their lives.

Follow Kevin Morosky on Instagram