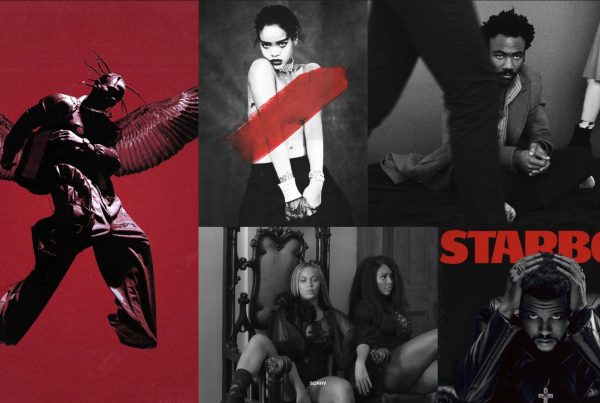

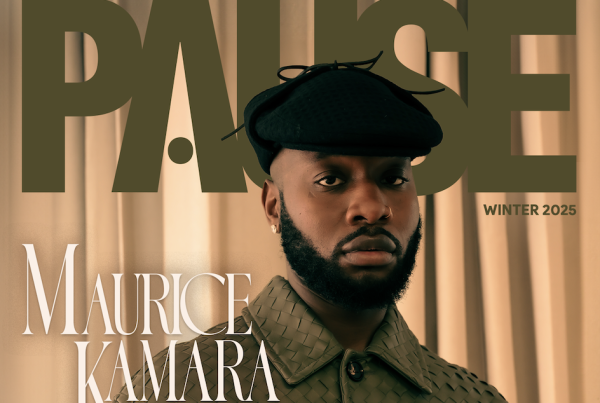

The Weird & Wonderful World of Leon Emanuel Blanck.

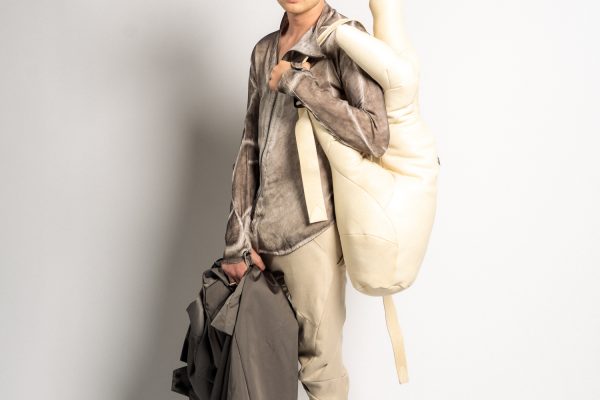

Whether you’re a seasoned veteran or just beginning your journey into the world of high-fashion, Leon Emanuel Blanck’s design language is one we can all see in ourselves. An infatuation with the human form rules over the Berlin-based designer’s outlandish creations, laying down signature stylings that make his pieces true to him – and him only.

Lining up with an anti-conformist approach, Blanck leans into Berlin’s dark aesthetic without having it dominate and directly inspire his entire output. From goat bags and an obsession with asymmetric patterning to studying and realising the processes of life and death, Blanck’s wholly unique approach derives from the black space that reflects across from conventionality, the void that many designers refuse to look into. More often than not with Leon Emanuel Blanck, you have to see it to believe it.

Sitting down for a recount of his journey as a designer so far, his creative DNA, and what is in his future, Leon Emanuel Blanck let’s PAUSE in on everything we – and you – need to know. Check it out below.

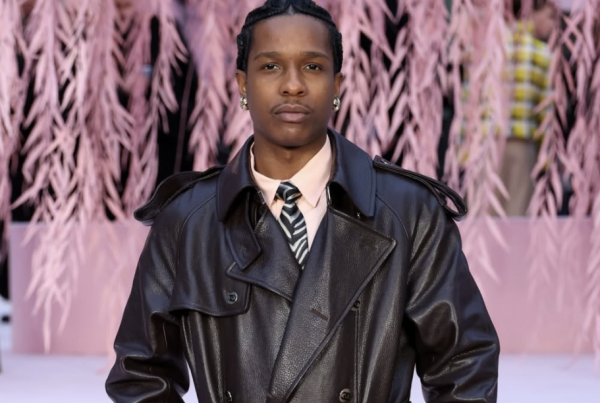

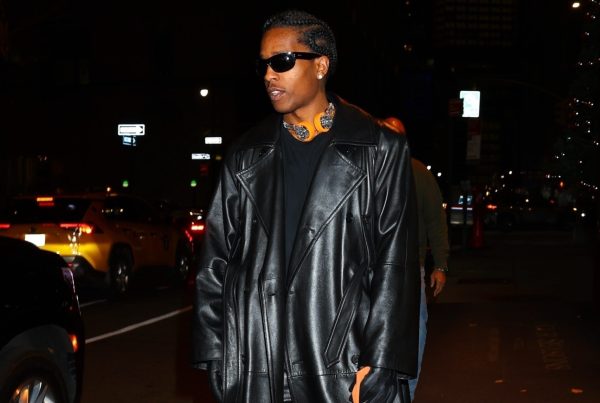

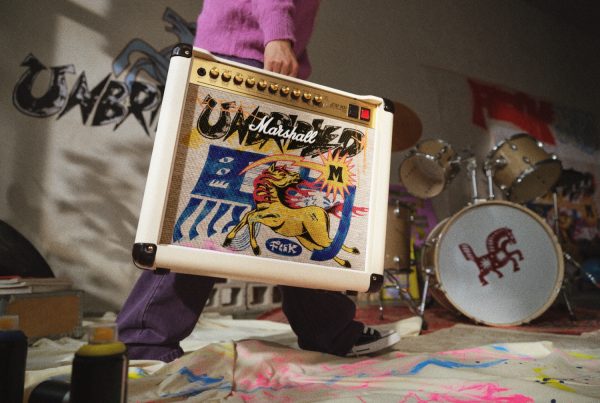

PHOTO CREDIT: Phillip Koll

Your work really caught my eye for a while now, so I just wanted to do a little bit more of a spotlight on you as a designer. For those unfamiliar with your rise in fashion, who are you and what was your entry point into that world?

So, my name is Leon and I started the label in 2012, and presented my first collection in Paris in January 2013. That was actually my first ever showing of anything that I had done and I had a little showroom in the Marais, just by myself really. I hadn’t done any internships or fashion-related work beforehand, so it was really just my first go at anything. I had this initial collection of eight pieces as well as a sculpture that were very much related to one another. Then I caught the eye of several, let’s say, “nice stores,” and actually from then on I had my first two orders. At the time I was just working by myself, and then it gradually evolved into what it is now.

Nice. So you had no contacts when you went to Paris for the first time?

No.

Wow, okay.

I really just took a train from my hometown, at the time it was Heidelberg, not Berlin, and just went to Paris. I don’t speak French, it was just German and English, really, and I kind of just went through the Marais because I had known that that was an area where you would show something during Fashion Week. I walked from gallery to gallery asking if I could show the collection. And at one point, some lady that was restoring art said, “you know what, you can show down here… I’ll go upstairs.” And that was a really good deal. I mean, when you’re in the middle of fashion week, I suppose you can’t get a much better deal than that! That was the beginning of the brand. And then from there on, I produced the first orders myself, and then had my first seamstress, and later on a pattern maker, and so on, and so on. I then moved into a small garage, from there onto a bigger studio.

Obviously, the first thing that stands out when you look at your pieces is your varied use of materials, often intertwining them for a reinterpreted approach to more heritage looks. What stemmed your initial interest in fur in particular? I know you had an interest in working with it at the very beginning.

Yeah, so that actually comes from the memories that I have from when I was very little with my grandmother and my mother, especially in the wintertime when it was really cold. They would wear fur coats, and I just remember that I was always hugging them. I really was always drawn to that material, and I worked in the fur industry during my studies. I always drove from Heidelberg to Frankfurt, that’s like an hour with a car, after school to work with Greek furriers in Frankfurt, and that’s where I got to know the machines, the materials, and all of this, and I did that for maybe two years of my studies, almost every day of the week. That got me the “know-how” to work with the material, and that was really the starting point. The great thing is that these furriers I worked with, they were so hands-on and they were so orientated to get things done, rather than speculating on what the best way of getting something done was. There really was always this, “what’s the smartest thing to do now?” It’s whatever it is, you just have to get to a certain state afterwards, and I found that fascinating, rather than this perfectionistic idea of how something is done in the textbook.

I remember seeing an interview of Rick Owens once, talking about that process and how you continually plan and try and curate something that you really love, but at the end of the day, you do need to get your hands on it. But yeah, staying kind of early in your development as a designer, what were some of your earliest reference points? I’ve read about your interest in sci-fi movies and directors and horror games, but was there a light bulb moment for you where you knew you had to translate what you were seeing into something physical for yourself?

So for me, the most interesting designers or ideas that were in the air or seen throughout the world were always people that had a very strong idea of how something would look, and you wouldn’t have to give it a name or a logo to necessarily understand it. It’s very apparent just to see the form. You know what it is, and I thought that was the go-to idea. That had to be the base of things.

I always thought that putting a name on something would be something that may be interesting later, but much like a drawing or a sculpture, you wouldn’t put a name on that. You might put a little signature somewhere, but you wouldn’t write your name on your artwork.

So, that was the base anyway, and then I was always interested in draping materials rather than making a pattern from a 2D starting point, mostly because I found these stand-up forms extremely boring and not challenging. Why would I want to learn something that someone else is already doing so amazingly well? Why would I, just speaking for myself, learn how to make an amazing suit when you can really just go to Saville Row or any amazing Italian tailor and they’ll make you the best suit ever?

While I really appreciate that, don’t get me wrong, I think it’s absolutely amazing what they’re doing, it’s just not my thing, right? So I thought, what am I interested in? I was always extremely interested or intrigued by human form and bodies. I really just started forming the human body and draping a pair of pants on myself, and then that was the starting point for the whole “Anfractious Distortion” universe. For me, something very spectacular came out of it, something that looked like it was grown, starting from a tree almost. And I remember taking those legs off and then that having this effect on me, like, “okay, that’s something.” That was really the “big bang” for the whole idea of creating. The seed.

You mentioned it there, but I was going to ask about “Anfractuous Distortion” and the process of analysing and using the human body in design. One of your earlier collections was about the process of rigor mortis, and that really intrigued me because it’s quite dark in its nature, but it is very alluring in terms of structure.

I was interested to hear if there are any other kind of life processes you’d like to explore creatively, because the possibilities with the human body are endless. Is there anything else in that area that you gravitate towards?

So, “Rigor Mortis” was quite strong in this sense where if you’re talking about human life and human form after your passing, it would occur naturally. The idea was that when you end up wearing a jacket that has had that rigor mortis treatment, you would give it some life back because you’re breaking it in again. But it’s very hard to further develop that.

I do have a collection that’s out, the Winter 2024 collection, which is called “Memento Mori,” that plays on the idea of life and death and distant past memories of things you’ve liked in your life and things you’ve dealt with, as well as what that means: “remember you must die.” It represents what that means to us or to me and to what I’ve been doing in the past 10-12 years with the label, what materials I’m using, and what procedures I’m developing.

To come back to your point, “Rigor Mortis” is so far the only one of those heavy treatments that has a deeper sense to human life. I mean, there’s one that we’ve used which is called “Symbiosis” where two things are, let’s say, combined through usage of the same material, which is a sort of resin that I had developed throughout the years. And then you rip the piece in two and have two pairs of shoes that were initially connected, but are now disconnected. That’s one that I would probably throw in within the same idea field, but it’s not quite as strong. Not as heavy thematically.

You’ve curated an ethos and a design DNA, and in a broader sense, it looks anti-conformist.

How hard is it to actively subvert outside influence and trends? Is it at times difficult to stay true to what you originally plan out? Or is that just a part of evolving as a designer?

I wouldn’t really say that I’m influenced by trends, but I don’t think that’s true in terms of how you can’t escape things. There’s never a part of me which would be like, “right, so what’s in now? Let’s do that.” I really don’t care. I’m just going to make some collections and sometimes it has a very strong theme, other times it’s maybe just an addition to past projects that I had developed. I truly do not care about what’s in or what’s not in.

I ask because I did a piece on it recently, about the death of trends. I think people are starting – as a consumer – to definitely become more aware and trends are turning over more quickly, and thus they’re inevitably going to die quicker.

When you were younger as a designer, maybe you were more influenced by things around you. But I suppose as you grow as a creative, do you just evolve to the point where you just cement your vision?

Yeah. I would even say that I was more radical when I was younger. Let’s take the first collections, they were either black or they were white, and there was this seriousness about it. I would say that I was quite serious about things, and I know we don’t know each other much, but I’m quite joyful. In recent years, I’ve kind of gotten into things being more fun for myself actually.

They’re tongue in cheek…

Yeah, exactly. You kind of play with the idea, you know? If we’re talking bags, you make a handbag and then it’s a hand. Okay, right. It’s a bit of a dad joke but you know, it’s made in this kind of way where you don’t really take it as seriously. I’m making a collection called “Memento Mori,” and I’ll make a horse head bag and then it’s made from horse leather.

I recently saw the goat bag!

Yeah, the goat bag! This was at the time when all the labels were making you know, these little animal bags. I think it was also quite in for the Chinese market, because they have the year of the rat, etcetera. And then I was like, “all right, guys, come on. Let’s make a good goat.” I think it was the first one of these bag situations that I started.

Yeah, it feels strange that nobody did the goat first to be honest.

Yeah, it doesn’t really make much sense. But people were going towards the dogs and things like that.

In terms of Berlin and Germany, I went a couple of seasons ago for their fashion week. I picture it as being attached to freedom mixed with certain elements of rebellion and things of a Gothic nature.

How much do you take from that and put into your work?

It’s funny, because I started the label when I was still living in a smaller town. So, my influence was more or less what you mentioned before. Sci-fi movies, computer games, some of these great creators like (Luigi) Colani, (Zaha) Hadid, just to name a few. The ideas were found in movies like, you know, Dune (1984), or films like that. I found them extremely interesting. Or even the Terminator (1984) movie, the first and the second one. Akira (1988), like these kind of things I found extremely interesting. Gothic was, funnily enough, always something that other people said about it. I didn’t get it. It goes hand-in-hand really well (with me), I really enjoy being here. I think it adds to the story, right?

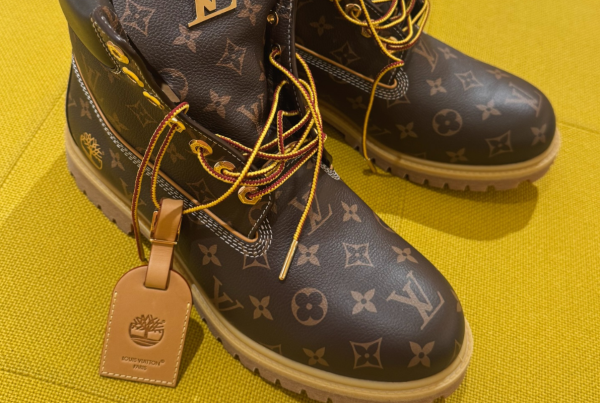

I think your approach to footwear is fascinating, because notoriously footwear is quite difficult to design and shape, and it takes a lot of samples to get right. Particularly with your subversive approach to design, what was your biggest challenge in translating your design DNA and placing it across footwear silhouettes? Because distorting footwear seems like it takes a fair few tries to do.

It took me several years until I launched footwear. It really was a struggle to find a shoemaker – since I’m not a somebody that makes them – that was willing to try out something that was not a particularly normal style of pattern-making for footwear. Normally, they’ll have patterns that are good to last, and that’s how they do it. Again, I have nothing against that, I just don’t need to do the same thing that’s been done before. They’ve got a formula of how to do something perfectly. Then, I got to meet somebody through a common friend of mine, Cecchi De Rossi, a shoemaker, Dimissianos & Miller. They have a shoe brand and we really got along super well. It must have been 2016, and they invited me back to Corfu to try out what I had in mind. His father was a shoemaker for around 60 years old or something, and he just actually took over that business anyway. We tried it my way, basically forming the left and right foot, and then translating that towards what I would want to use. I remember him saying that he found it very interesting that the patterns I had created worked better, and don’t quote me on better, but works better for lasting, because you don’t have to push it over so hard. I found it interesting, because again, it goes well with my idea that there’s no right way of doing something; there’s just several ways.

It went pretty well for several seasons but then we had bigger orders, so we had to find a new person that would make our shoes. And I, through a common friend again, found someone in Italy. And this guy is our sole and only shoemaker. He is 73 years old and works with his wife… the guy’s incredible. He doesn’t speak a word of English, so we talk with his son, who speaks English – or me on Google Translate – and he’s absolutely amazing, he absolutely nails it, and he completely understands that we want to get away from. Giuliano said that since since he’s been working with us, he really finds joy in making shoes again, because it’s so different than what he’s been doing for 60 years.

I’ve been working with him since 2018, so a while now. If I work with a traditional shoemaker on traditional shoes in my way, it’s quite simple, because you’re working with form on last, which is sort of easier, but then if I’m working on a different scale and I change the whole procedure on how, let’s say, a sole looks, then we’re getting into a field that’s getting harder, especially if it’s handmade. If you’re making so many pairs, you can make a form and it just spits out lots of the form, but it’s all handmade, it’s all built like an actual boot, which is the interesting part.

That’s great.

Obviously you stated earlier that in the earlier days, you kind of went black or white and it took a very straight line approach in terms of what you wanted to do with each collection. Sometimes, simplicity is best. How important do you think reductionism is in your work? Is taking away elements of an initial design idea just as important as adding to it as you go?

Well, it’s a good point, you know, this idea of like killing your darlings. I have that in my mind a lot. In the very beginning, as I said, I was more radical when I was young. I was very strict with this idea of not adding anything else, I didn’t need anything from traditional clothing to make this piece of clothing; that was always the idea. But in the last few years, I found an interest in actually adding traditional bits and pieces for a reference point of understanding, helping what I want to show here, because there’s a reason why, let’s say, a certain coat has a big lapel. It shows something, it delivers a message, and I think what I’ve learned throughout the years is that certain ingredients will deliver a certain message.

Looking ahead to the end of the year and 2025, what are some challenges you’re looking forward to tackling?

I think they are probably always the same, you know. If you’re a smaller brand and you’re in an environment such as Paris Fashion Week with big brands, there’s a real challenge to keep up with producing something valuable that people actually understand. But I feel like I’ve thought of that quite well throughout the past 12 or 13 years.

I’m independent, so that’s a challenge that means you have several employees, you know, you’ve got something you’ve got to keep going. That’s such a challenge, to keep everyone happy, afloat and keep everything working. This is probably the biggest challenge, but in terms of what I’m looking forward to… I’m making a new winter collection. It’s based around a motorcycle that I’m building right now, sort of from scratch. It’s a rebuild from a classic motorcycle, but I’m making it obviously look more or less like one of my sculptures. Yeah, and then built on top of that there will be a pretty big collection, but for the first time I’m also designing it differently. Before, I would only add to the universe and to collection ideas, using the pieces that would work with this kind of vision, but now I actually draw things. I draw looks that I want to make so I kind of already know what the collection looks like before I do it, and normally it’s the other way around, so I’m working differently for this collection. I’m also working on a new line, which is called LEB. Coming back to your thought of reducing, this is like a drawing where you have certain lines that are the most effective and the most direct. I’m trying to reduce all of the little scribble lines that are unnecessary, to strip it down to the bare skeleton of fractures and distortion. So, very much just about form, solely form.

Well, I’m looking forward to seeing them. I’ll be keeping an eye out.