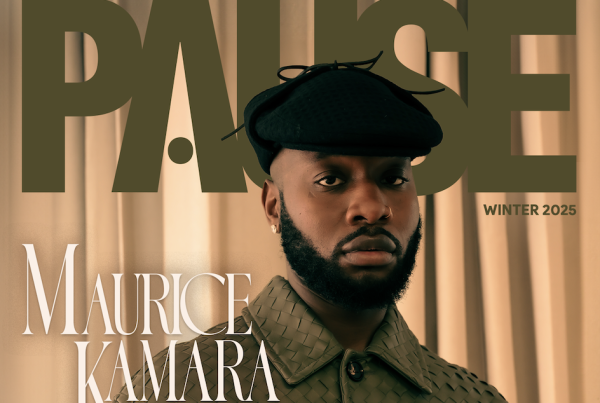

What stopped fashion’s virtual revolution?

In the socially distanced days of early 2020, with physical catwalks on pause and our wardrobes reduced to sweatpants and pyjamas, digital fashion emerged as a hot topic within the fashion industry. Entire collections were imagined in pixels, not fabrics. Designers dressed avatars instead of models. And luxury brands dipped a pointed toe into virtual waters, captivating the imagination of consumers and investors alike. With words like augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) creeping into the zeitgeist – many predicted the complete disruption of traditional fashion, ushering in a new frontier of digital fashion.

Fast-forward a few years, and the reality is a little less sci-fi-chic than most expected or forecasted. Despite its well-deserved initial buzz and billions in investments, in a post lockdown-slash-post-pandemic world, digital fashion has largely failed to break into the mainstream. At one point touted as the sustainable, tech-forward substitute to the archaic approach of physical clothing, the trend seems to have fizzled out as quickly as it flared up. But what is behind the failure of digital fashion to fully integrate into everyday consumer culture?

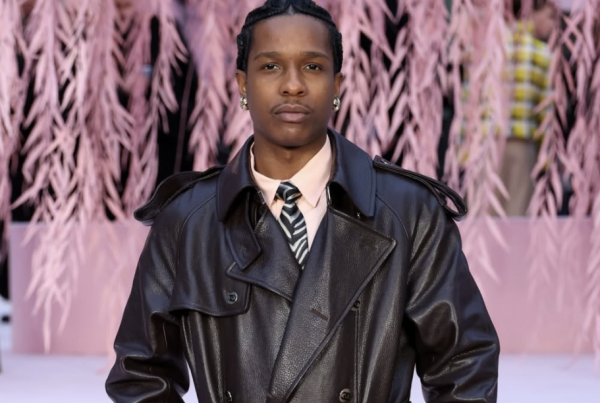

PHOTO CREDIT: showstudio

A product of its time. The rise of digital fashion was no accident. As lockdowns swept across the globe in early 2020, life as we knew it was brought to a stand-still. Runway shows were cancelled, retail locations were closed, and brands were forced to think fast; evolve or die. As consumers turned to the digital realm for entertainment, social connection, and much-needed self-expression, e-commerce boomed, and a pandemic-fuelled surge led to the creation of the digital garment: clothing designed exclusively for the virtual world and worn only in the virtual world by avatars in online games, or digitally superimposed onto influencers snaps for the ‘Gram. During this period, the appetite for the virtual fashion industry was at fever-pitch. With the rise of NFTs and blockchain technology further fuelling investor optimism, this new approach to fashion promised a fresh out-the-box-take on sustainability, inclusivity and a future where consumers no longer had to wait to wear the latest trends but could do so with a click of a button and without the environmental costs of traditional fashion.

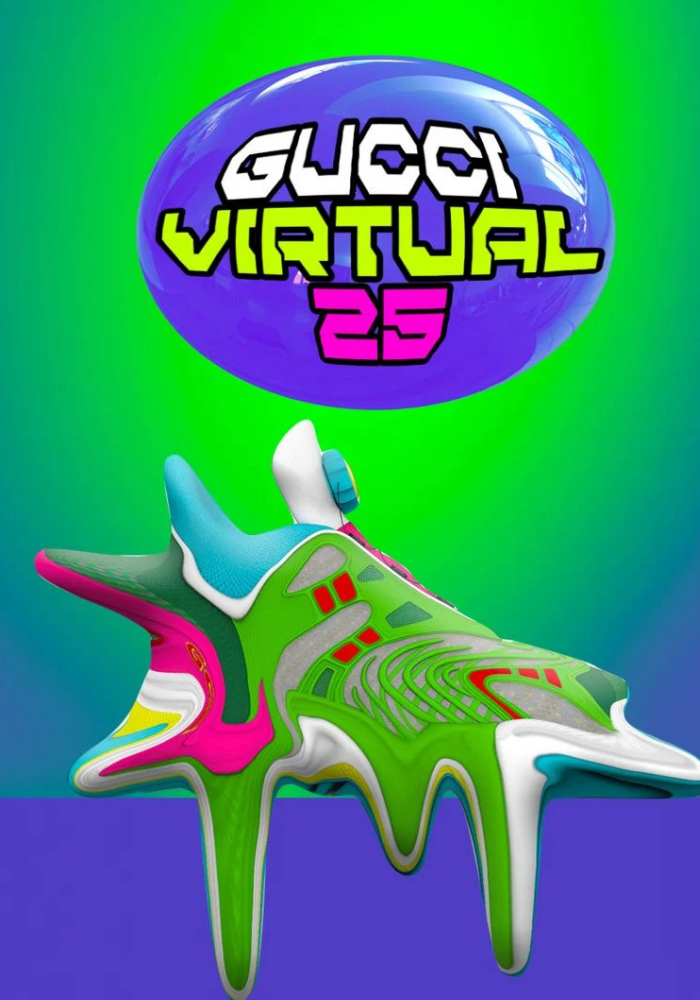

Fashion’s major players like Balenciaga, Gucci and platforms such as Decentraland and RTFKT Studios all threw their hats in the ring, emerging as exciting new avenues for creative explorations. Gucci partnered with Roblox and released a pair of digital sneakers (they couldn’t be worn in real life, of course, but they were Instagram gold). Ever-experimental, Balenciaga created an entire virtual video game, Afterworld, to showcase its Autumn 2021 collection. Not wanting to be left behind. Looking to maintain relevance and stay ahead of the curve in an increasingly digital world, influencers and celebrities alike also got in on the action; embracing virtual clothing via posting on their feed wearing outfits that could only exist in the digital space. But then the hype died down.

PHOTO CREDIT:DressX

Like many other pandemic era trends, digital fashion couldn’t quite contain its momentum and despite the initial excitement, once physical life resumed, and the world slowly returned to normal – the novelty of owning a digital t-shirt that you couldn’t wear to dinner wore off. While augmented and virtual reality provided a fun and unique experience during the lockdown era, post COVID, the inherent lack of practicality and tangible value made it difficult for consumers to justify spending money on something that only existed in the virtual realm. While it had been a novel idea to post a CGI couture gown making its way down a CGI runway, reality soon set in that these digital garments, unlike physical clothing, did not serve the functional purpose of dressing for real life experiences. Digital fashion had no utility outside of its niche. Buying digital fashion meant buying something that you could not physically wear, and for consumers who were accustomed to purchasing craftsmanship, fabric and fit – the emotional and practical value of digital garments just wasn’t the same. However, the issues did not stop there.

For fashion enthusiasts, tech insiders and those in the know, digital fashion was the future. However, for the average consumer this did not resonate, and the mainstream adoption of digital fashion started to experience serious hiccups. Fashion is emotional. Buyers have long held emotional connections to their clothing. The feeling of a perfect-fitting pair of jeans, finding the picture-perfect cut for your t-shirts or the way an outfit makes you feel when it comes out as you saw it in your head. These emotions cannot be replicated, and this is where digital fashion struggled. Fashion needs to be felt, both physically and emotionally. Purchases need to feel meaningful. However conceptually interesting the digital fashion collections were, they still felt disconnected from the emotional experience of buying and wearing fashion. Ultimately for many, the value proposition was not clear. Why buy a virtual outfit that can only be worn on a platform like Instagram or Snapchat, when the same funds could purchase tangible items in the physical world that could be worn at any time and place?

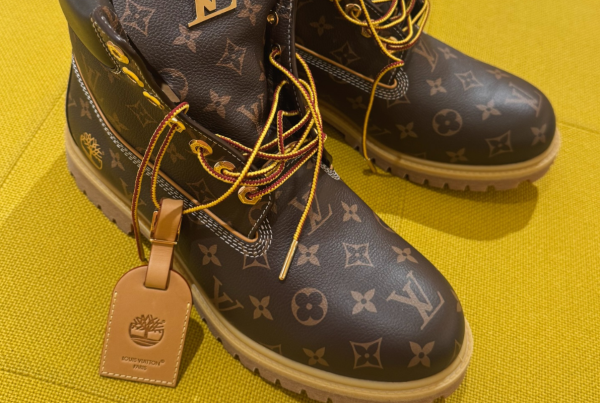

PHOTO CREDIT: Gucci | Gucci Virtual 25 Sneaker that can only be worn in AR.

At its core, fashion is a tactile experience – the swoosh of a shirt, the weight of a good t-shirt or the experience of putting a good fit together. And while the metaverse had plenty of options for your digital self-expression, it couldn’t replicate the feeling of wearing something that makes you stand taller or have you feeling yourself. Therefore, as the lockdown restrictions eased, consumers wanted that old feeling back. With an almost feral return to traditional fashion – consumers wanted tailoring, Aime Leon Dore crewnecks and statement shoes – the real stuff. And brands wanted to give to it to them. As the pandemic began to wane and people returned to in-real-life interactions, retail shops opened back up and sales began to soar, even fashion weeks went back to in-person shows. Vogue Business wrote that live streams of fashion weeks had “surprisingly few takers” once in-person events resumed. The people had spoken, and it was clear; digital just wasn’t the same.

The sustainability of digital fashion also became a point of contention for a sector that had positioned itself as a more sustainable alternative to fast fashion. Experts began poking holes in the eco-conscious claims of digital fashion and calling out the environmental impact of maintaining blockchain networks. The energy consumption of NFTs and blockchain-based fashion items can be sky-high. But with lifecycle of product being produced ending at a social media post, evo-savvy consumers started to bemoan whether this approach was really a greener solution. Also raising red flags for consumers was digital fashion’s reliance on emerging technologies like NFTs, blockchain, and AR/VR as well as issues of data security and privacy. To enjoy the digital fashion experiences, users needed to jump through a series of hoops to create a digital wallet, meaning providers would have access to users’ personal information.

PHOTO CREDIT: The Fabricant x Puma

While fully virtual fashion may have failed to achieve mainstream status, the hybridisation of digital and physical fashion continues to be explored and incorporated into the fashion collections of luxury brands like Gucci and Balenciaga. Both brands have experimented with AR technology, allowing customers to see how garments would look on them without trying them on in-store. While brands like Puma and Nike, have integrated virtual try-on features into their e-commerce platforms, merging the digital and physical realms in a way that enhances the shopping experience. The continued integration of digital experiences into physical fashion is an exciting prospect, but its ultimate success will hinge on its ability to meet the emotional, practical, and ethical needs of the everyday consumer.