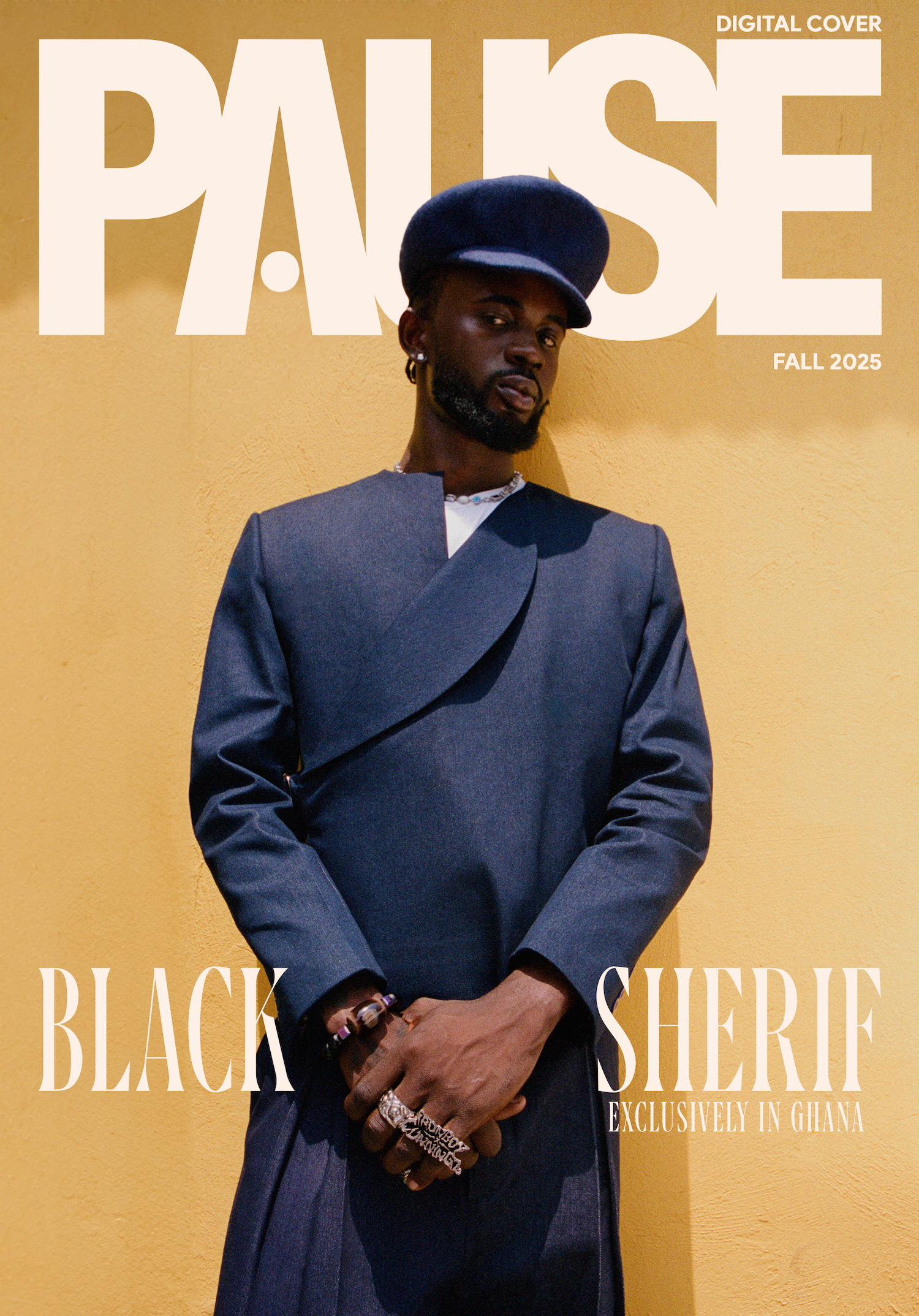

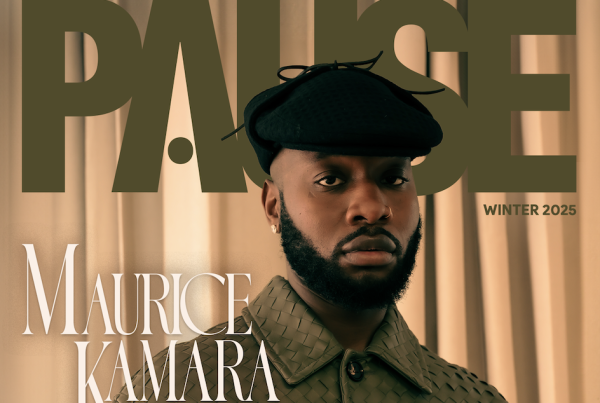

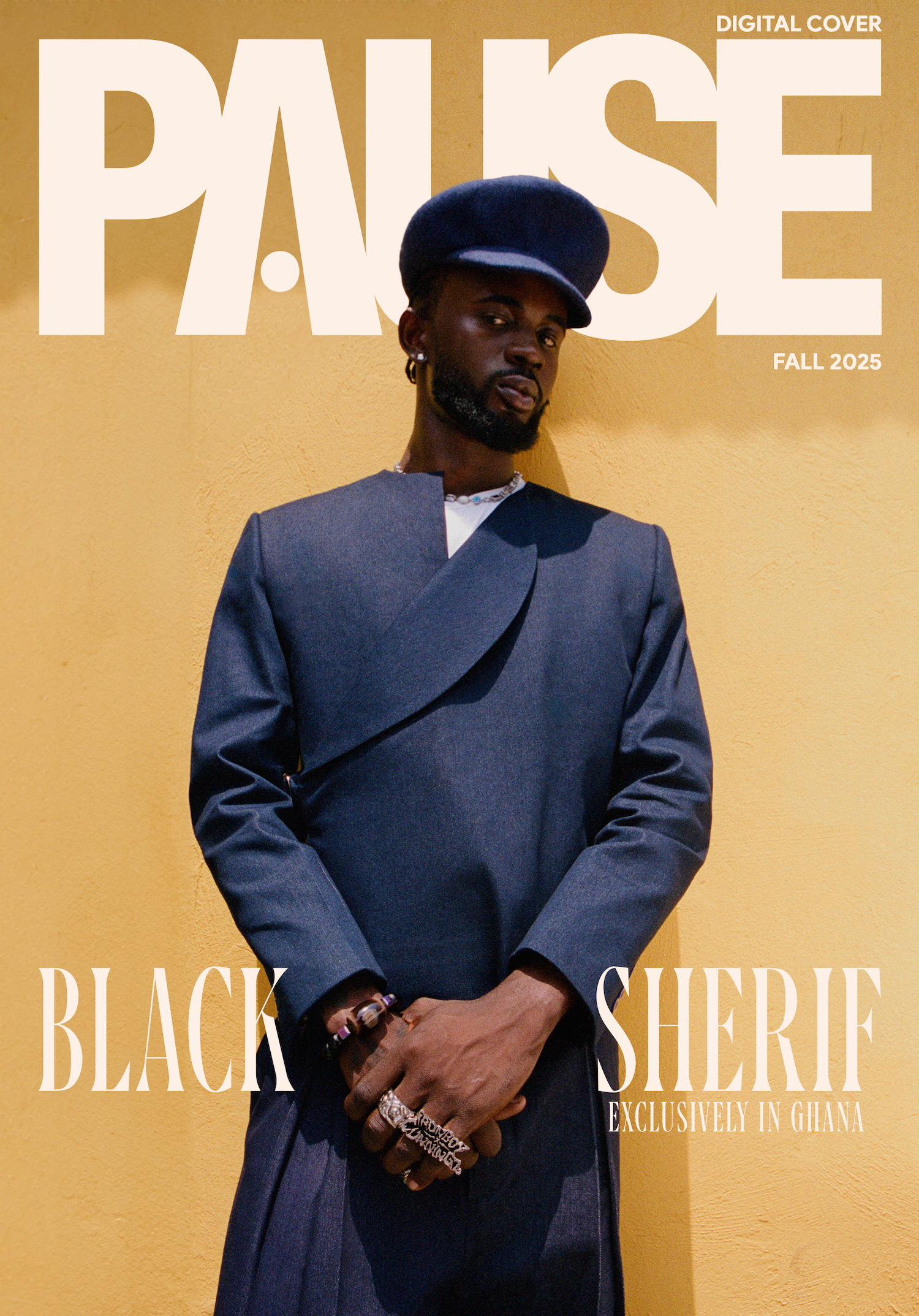

PAUSE Meets:

Black Sherif

Talks Konongo Zongo, self-reflection, & shaping personal evolution.

“I believe that I’m part of this world, I’m a part of a collective… so if it’s personal to me, it will be personal to other people.”

Black Sherif moves between two worlds. In one, he is simply human: raised in Konongo Zongo, nurtured by his mother’s warmth and driven by his father’s relentless work. In the other, he is an artist: a voice of rhythm and melody, translating his own life into music that carries memory, emotion, and intention across continents. From highlife to drill and reggae, every note is rooted in home, yet limitless in reach.

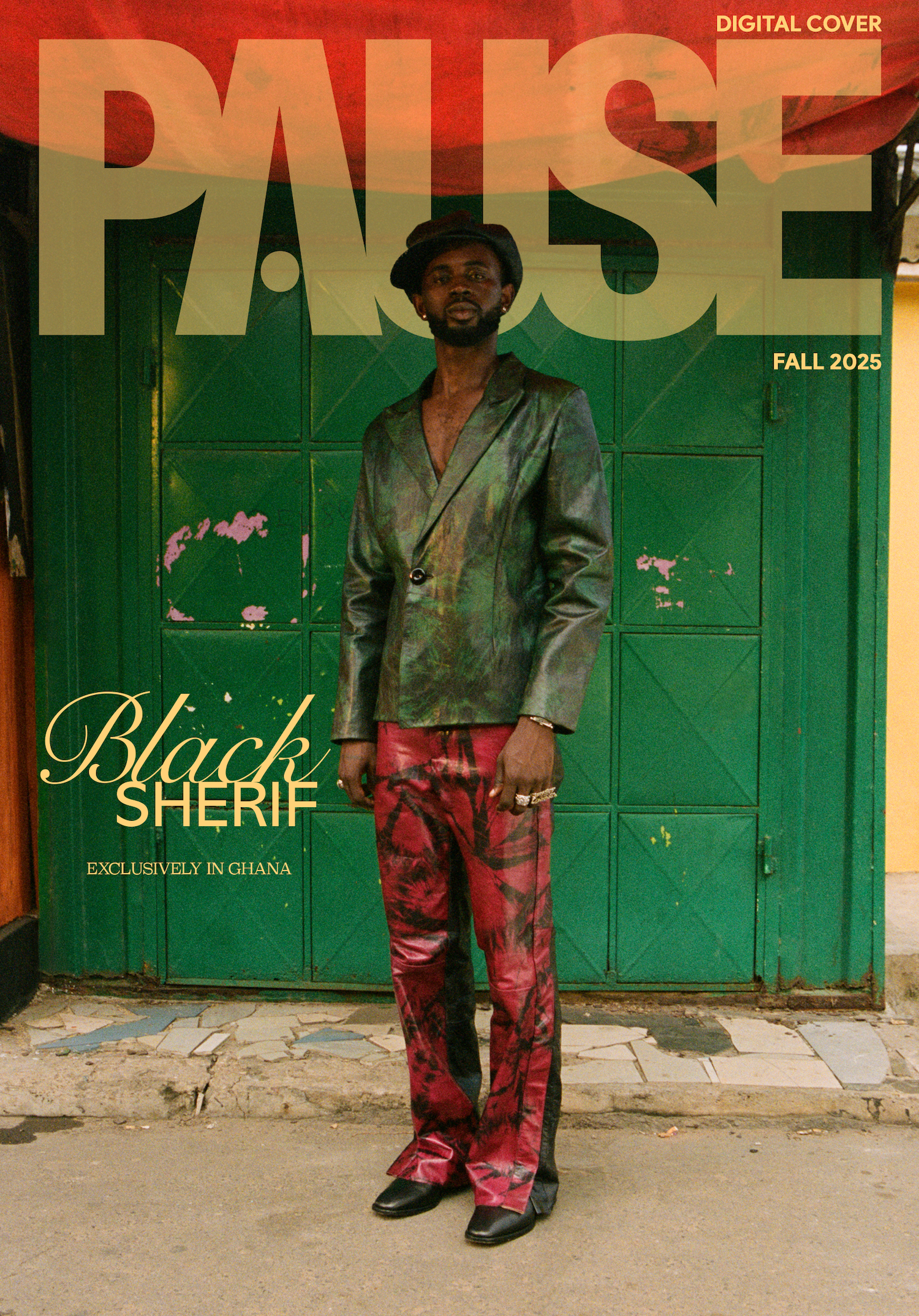

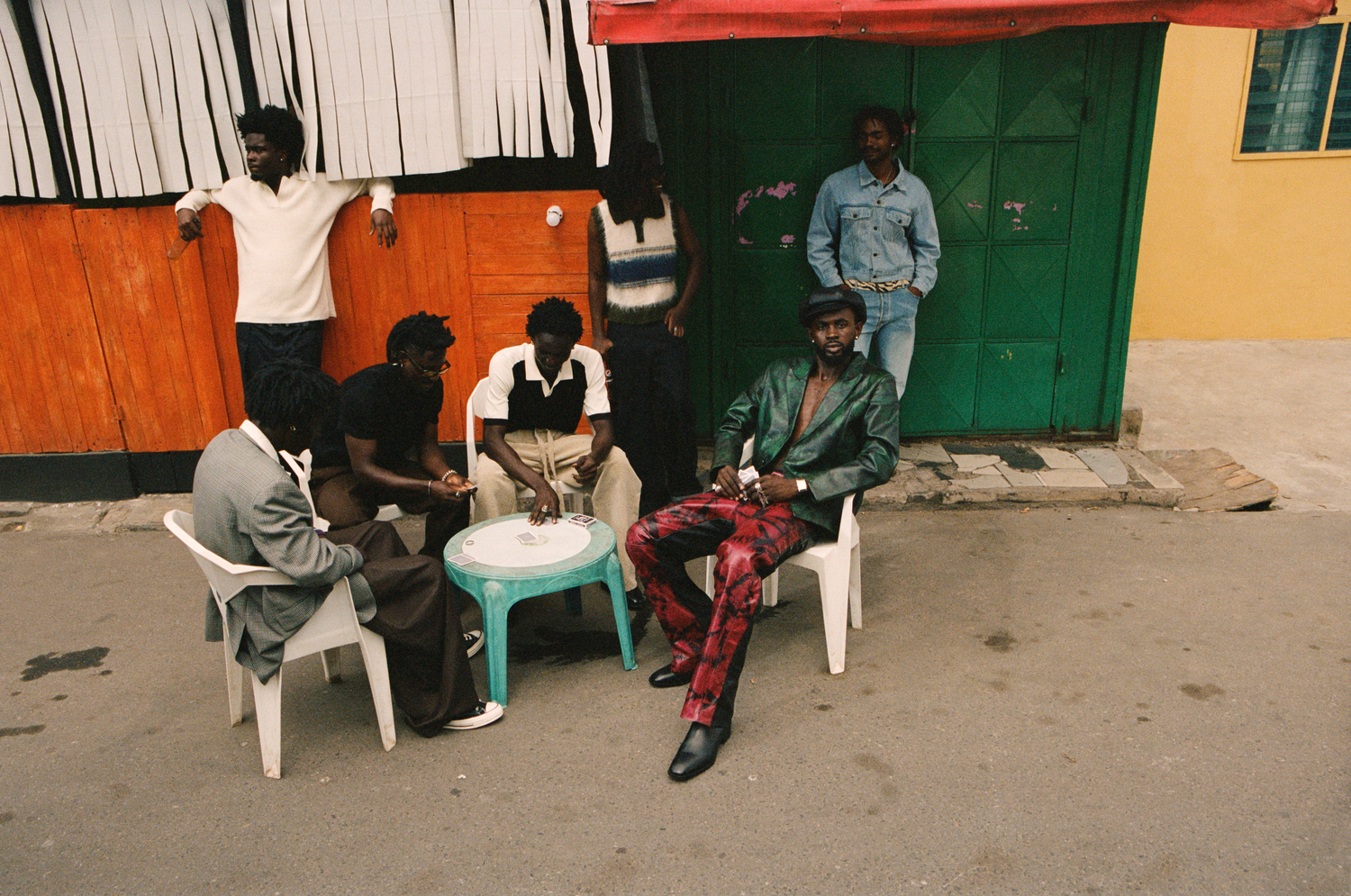

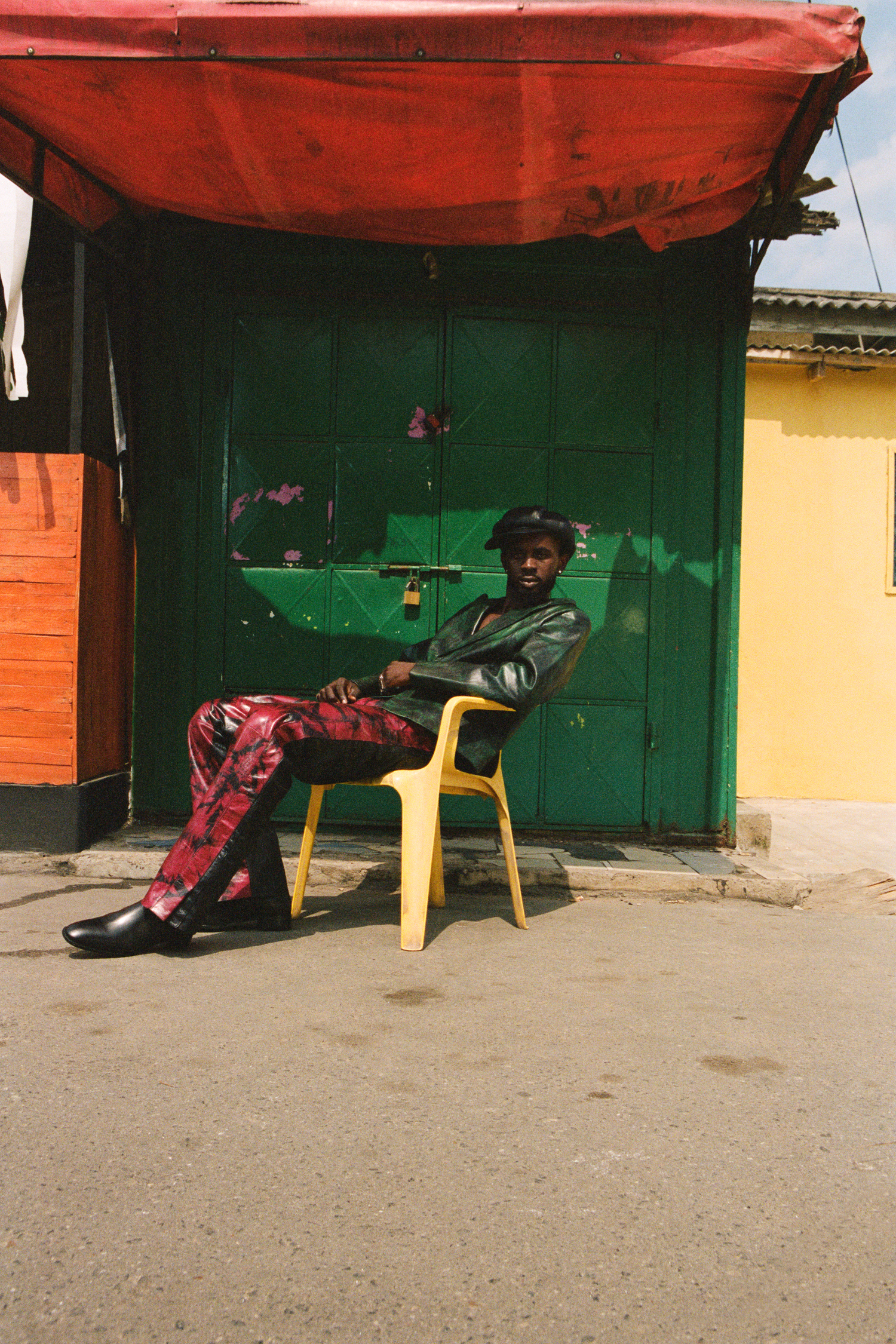

PAUSE Magazine’s Fall 2025 cover captures him exclusively in Ghana, revealing both halves of his being. Tender and ambitious, reflective yet commanding, Black Sherif inhabits a space where the streets and friendships that shaped him are more than backdrop, they are the pulse, the compass, and the very heartbeat of his own artistry.

Read the interview and watch the short film below.

Kwasi Paul Dadie Anoma: Set / Uptown Yardie London: Minott Hat / Christian Louboutin: Samson Flat Shoes.

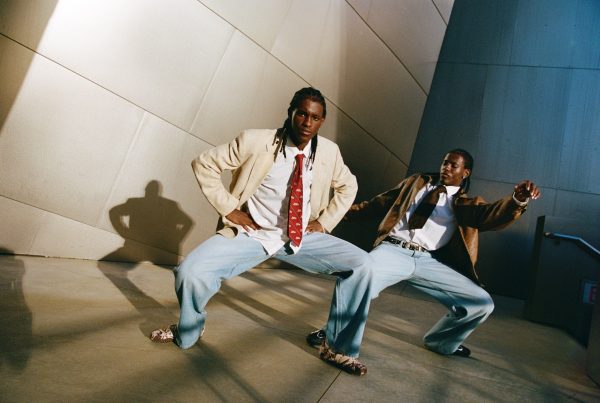

Earlier this year, you shared with Reprezent Radio that, if not for music, you might have carried on your father’s business selling car parts, a thread back to Konongo that felt essential to capture. That’s why we placed other young men in the shoot, echoing the friendships that shaped your beginnings. For me, as a Ghanaian, grounding this work in your origins was vital, so others can witness just how aspirational your journey truly is as we visualise the opening scenes of a story still unfolding in real time.

Your sonics are a form of telecommunication, frequencies that people don’t just hear, but also have to feel and think through. If we step inside that experience, what does it look and feel like for you?

I think it’s a representation of how my mind works, how I love to describe stories. It’s actually something I can’t even help. [Things like] making melodies, right? Some of the melodies that I make, some come with words, then [others] come with feeling. There are some songs of mine that I listen to and I feel different each time that I listen to it. Like, every single time that I listen to [a song], I can feel different about it. It’s really a representation of how my mind wants to tell my own stories, or the types of feelings I want to give out to people who also listen to it.

Can you share a moment when you felt this most with an audience? Or is it different every time? Like what you described with listening to your songs?

I’ll say, on my first show, my first date in London, I was performing my song “One,” and I was crying. When I was on stage, it took me back to one of my vocal lessons with my vocal teacher. We were reading this book… I forget the name, but it said: “Expressive singing always brings a reaction. The audience, they cry, tap their feet, or sway to the music.” So when I was making that song in particular, I just knew at some point in the journey, or within the lifetime of the song, I’ll listen to it and cry. And I got on stage, and that was the moment. In that moment, I was singing, but I was also reminiscing, thinking about the real-time results I was getting, the real-time results from the intentionality of making the song, you know?

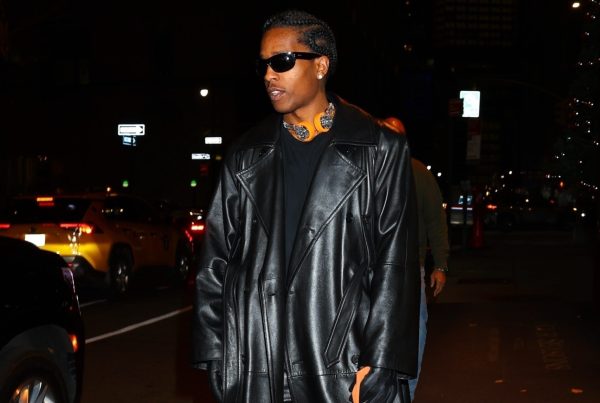

PALMWINE IceCREAM: Gye-Dye Up-cycle Leather Blazer / MBLO Up-cycle Leather Pants / Christian Louboutin: Samson Flat Shoes / Artist’s Own: Hat.

How do you make the production experience just as meaningful as the lyrics themselves? Speaking of being intentional, how intentional is the composition of your music?

It’s super intentional. Most times, I’m consciously intentional, even with words, sometimes I sacrifice words for melodies – because in that moment, when I’m creating, I believe it’s the kind of effect I want to have on the listener, or even myself. I don’t often care about the proper pronunciation of words, [I think] if it fits into the melody and rhythm I’m putting out, I just say it. At that moment, I just hope for it to make sense.

Your music often resists straightforward storytelling. Instead of neat closure, it leaves space for reflection and emotion. Is that a deliberate choice to push listeners toward self-reflection, rather than following a linear narrative?

I think it’s very natural. It’s natural to me, even as a person. I don’t even remember a time when I was able to explain my thoughts in a very straightforward manner. I think that’s part of the reason I got obsessed with making music, because that was the only place that I could freely express myself without constantly being misunderstood. I don’t really like vague answers and stuff, I love precision, and seeing things from a different perspective.

I understand!

Like, I enjoy music when it’s personal, and I enjoy making music when it’s personal. When it’s super personal, it’s the best. And also, I believe that I’m part of this world, I’m a part of a collective, so if it’s personal to me, it will be personal to other people, you know.

I also wanted to ask if your work often feels rooted in Sankofa, reaching back to carry what might be lost. How does that philosophy guide you personally and artistically, if it does?

Yeah, it really does. Even as a kid, I wanted to be different so bad, and it was something that I couldn’t help, you know? I find some comfortability in not being and not doing what everyone else is doing, and then allowing whatever I’m feeling, and things that I love to experience, come out of myself. The music I listened to, the pictures I saw, the performances and gestures that I loved to see, I do them all now. Most of that comes from very early influences, like stuff from my hood, conversations I heard as a kid about what it takes to be a good performer, who the good musicians were, what good music is. Those are all the things that influence my creation and my being.

You often talk about being free, or finding freedom, and we also all know you as a boundary breaker, and not leaning into predictability. But how did that freedom unleash itself?

How did I unleash myself? How did I find that freedom? Now, that’s a question. I’d say through music. If I remember a timeline of where I really wanted to put everything out and go all in, it was after high school, and then after that, the most precious thing in my life was me knowing that I could make music and write music. I think music gave me that confidence. It sounds really generic, but that’s really what it is.

AMI Paris: Belted Mac Bandana Midi Dress, Wide Trousers / Cartier: Glasses / Kiing Daviis: Shoes.

When did your fascination with music begin?

I’ve always been a listener of music and I’ve been enjoying music since time. I’m from a really religious, Muslim background, so I never knew I could make a life out of music. I’ve said it so many times – when I was in high school, in year two, and three, my classmates enjoyed my voice so much. I’d cover songs for the students and that gave me a different kind of feeling about my ability. Writing music then became part of my being, I began to understand myself more through making music and embarking on my music journey.

I must add, you are a natural. From everything I’ve watched and researched, to the way you use your words, even if you’re just talking to someone, it seems very poetic.

There are a lot of things I have learnt about myself. In interviews, I can get asked a question and I’ll be like: “Yo, I’ve never really thought about that before,” and I’ll start to think, even after the interview once I’m home, and I’ll take it all in.

Casablanca: Set / Axel Arigato: Slow Runner Shoes.

Your artistry feels embedded not just in your DNA, but in your world view. While your father’s influence is often highlighted, I want to understand how your mother and her career as a seamstress shaped you, and ultimately influenced Black Sherif?

When it comes to my human side, it’s really [because of] my mother. For the first 10 years of my life, I was with my mum. I’ve never actually lived with my dad before – I just knew he was a hardworking man and he was good in school. He is brilliant and hilarious too. But when it comes to me as a person, I’m more of my mother. Very calm, super chill, very low toned. Her aura is so serene. She likes hobbies, she has a lot, from this and that, to braiding hair. My human side is my mother and that’s where a lot of my nurturing spirit comes from.

That makes a lot of sense.

I also wanted to ask, your blend of highlife, reggae, drill, and more feels reminiscent of the diasporic soundscapes that grew in England from the 1950s, when African and Caribbean immigrants merged traditional sounds to create new genres from the 1970s onward that still communicate deeper meaning for generations like mine. As someone who resists categorisation, how do you think your sound is reshaping the identity of Ghanaian music today and for the future?

Hmm, I mean, it’s bringing some realness to it, you know, because I’m actually still figuring everything out. But I just know if there’s one thing that I’m bringing to the soundscape, it’s some realness. Yeah, some realness and some rawness into the music, into the melodies, into the being… because I love to experiment, right? But, when I started making highlife songs, I could write like ten verses in five hours. And sometimes when things come too easy, you don’t really rate them like that. The reggae, the highlife, that’s me. Even when I’m rapping the rhythms, the melodies, the scalings, the topics, the things that I want to talk about. And even perspectives that I bring to love music as well, like very romantic stuff, my perspectives are always so real and very raw that sometimes it brings me some… I won’t say problems, but it makes me anxious, it makes me super anxious.

Even in interviews, because these songs I’ve made are super real and in some of them I hide them in the melodies, and some of the stories that I can’t say I hide in the ad-libs, I hide them in the harmonies. But then when I’m at interviews, and I have to explain everything. So in the moment, I’m very, very anxious, and I’ll just start fumbling. And these are things I’m still finding ways to deal with.

Yeah, that makes sense.

Thank you. Your music seems to redefine growth at each step. How do you and your creative director, Farouk, ensure that those changes are reflected visually and conceptually, while also challenging audience expectations?

I think it’s so much trial and error. Try and fail, try and fail. Because, sometimes we spend three months, four months, playing dress up, shooting, scrapping the shoots. Like, we spend a whole quarter of a year working, then nothing comes out. But then we feel progress, you know. The conversations that we have, they feel progressive. And plus, we present our journey, right? So, when we get the best out of the sounds that we are making, the visuals that we are making, that’s what we present when we are okay with it, because we know the journey better than anyone. We know the Black Sherif journey better, we know how I want to present our art. Creatively and artistically, I think we are really present. We try to be very present with our growth. We are trying to create and make the thing and present it, and if it’s not getting to where we want it to, we just keep pushing, because we know it’s going to come out. And then when it comes out, we just put it out. And as time goes, maybe our methods will change, and maybe we’ll become super, super intentional or super this or that but like, right now it’s just a lot of trial and error, trial and error. But I guess we just don’t stop, we just make it.

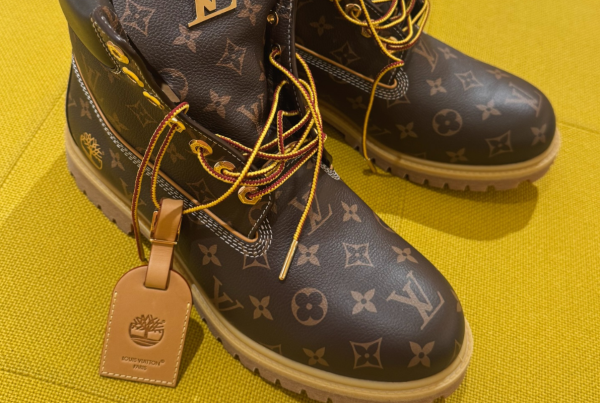

Yeah, it’s a learning experience. You’ve previously described music in terms of colours. If we shift that idea into fashion, what designers would you visually associate with The Villain I Never Was and Iron Boy?

Yo, there’s a billion thoughts in my head. The Villain I Never Was, I would say it was as raw as it came, super, super raw. I would say… The Villain I Never Was (would be) Yohji, I would say Yohji Yamamoto. Yeah, and then Iron Boy, I’d say is Alexander McQueen and Martine Rose.

I see that… the suit trousers that you wear in The Villain I Never Was album cover kind of gives Yohji yeah…

Mhmm!

How does your personal style support your personal evolution and shape your artistic expression?

I think it kind of extends my creativity, you know. It extends some creative rooms for me, because I’ll be in scenarios when I’m making music, and I’ll see some kind of shoe, and the shoe will take me back to a time that I believed Sherif was wearing the shoe. And then I’ll make soundtracks for that time, things like that, you know. Every time my style grows, I don’t let it grow without everything, like my skill sets, right? I see my style as kind of part of my skill sets, you know. So if it’s growing, everything needs to grow together.

Yeah, they’re both an extension of each other.

That makes sense. Does your love for performing get enhanced by the clothing choices you make? Do you see fashion as a way to communicate non-verbally with each audience as a part of the creative experience? Because I’ve seen you say that you like to make things very theatrically.

Super, super theatrical. And I wasn’t even a theatre kid, you know. I just feel like I have a lot of literature in me that I want to share. I don’t really know much theory about literature and stuff, but like, I live it. I live it, I wear it. I have very clear visions about performances. The gestures I make on stage are even super one of one, you know, like on the spot. I live with this music, I live with these clothes. And if I’m wearing the clothes, if I can wear it, I can perform in it. If I’m loving it, I can perform in it. Like, I have these Margiela Tabis that I think I’ve performed in twice. They’re so elegant, you know. The walking, performing, everything in that particular shoe, it feels so elegant, it feels so majestic. The last time I wore it was this tour performance, and I had this very blingy scarf on my head and that Tabi shoe, and I felt untouchable. There’s this feeling, I don’t know how to put words to it, but like, it influences the whole thing. The movement, the gestures, the dances, everything.

At my performance in Hamburg, I wore a suit and these Vivienne Westwood loafers, and I felt like Michael Jackson. So, if I am loving the fit, it influences everything about the performance. It doesn’t change the training that we’ve done to go perform with the band and everything, it changes how I want to perform. It changes every show and how I want to be seen at the show, how I want my art to be seen at the show. I go in the closet and I pick the stuff to help me be seen as that.

Yeah, that makes sense, and I guess it helps inform the set list and what you want to communicate to the audience.

Yes!

You’ve said dressing is a physical representation of the sound you create. Will your up-and-coming clothing brand extend that idea, helping to define your music and storytelling in another form?

I wouldn’t want to make my clothing about my music and myself like that. If I’m making clothes, I want to make clothes for my community. Even as a kid, I would go to the market and go tell my mum, “I need this.” I would love to extend clothes as part of my own journey… like a body of work. I don’t want people to buy my clothes because I’m Black Sherif or because of my music. I mean, I could influence it, but I want them to buy the clothes for the art, because the clothes are good, the quality, it’s its own thing.

You’ve essentially created a character that extends yourself while exploring Afrofuturism. Do you see Black Sherif as just an amplified version of you, or as a vision for how Afrofuturism can inspire a younger generation of Ghanaians?

To be honest, both. Like I’ve said recently, I’ve been speaking to myself. Is it third person or second person? I don’t know what it is. This takes me back to when you asked me how my mother has influenced me, you know, and I feel like when you see me in my hood, in my home, I’m my mother. But like, when I’m working, I’m my father. And that’s who Black Sherif is, it’s all one, it’s all one person. But then I am aware of how different I can be in different situations. That’s speaking about Black Sherif as a person.

When we go back to the emergence of highlife, it became a barometer for postcolonial public opinion, promoting unity and national struggle and helped set the groundwork for a new vision of modern Ghana. Similarly, your music transforms pain into possibility and, despite its grit and rawness, carries a sense of optimism. What do you hope to incite with your music in younger generations? And what is the most important message you want them to take away when listening?

I want them to take limits off their dreams, you know. I started taking limits off my dreams in the music even before I did it in my life, you understand me? These were words of affirmation and me taking control of my own destiny and saying things that I want to happen. It’s easy to break in the society that we grew up in because of how it is designed. The next person, if they were speaking about their dreams, would be laughed at and told it’s not possible. When I wanted to make music, I used to walk around with books and a pen. 11pm, I would sit on top of the gutter in front of my auntie’s house, and I would sit there and start with headphones, writing. It didn’t make sense to the people around me, they think you are just another guy. Like, there’s no way you think you’re going to take a pen and a book and then you’ll make music and become big. There’s no way you are here thinking like that. But the kids in my hood will tell you like, the ones that know me, I can see it in their faces when I go back there that they feel so far from me. Those are the things that bother me sometimes. Those are the things that are worrying me right now, because it confuses me as a person. I know how big we’ve become, but then that’s what I also want them to take from my journey as an artist and as a songwriter.

Follow Black Sherif